Notes on a Writing life 38

14 June 2022

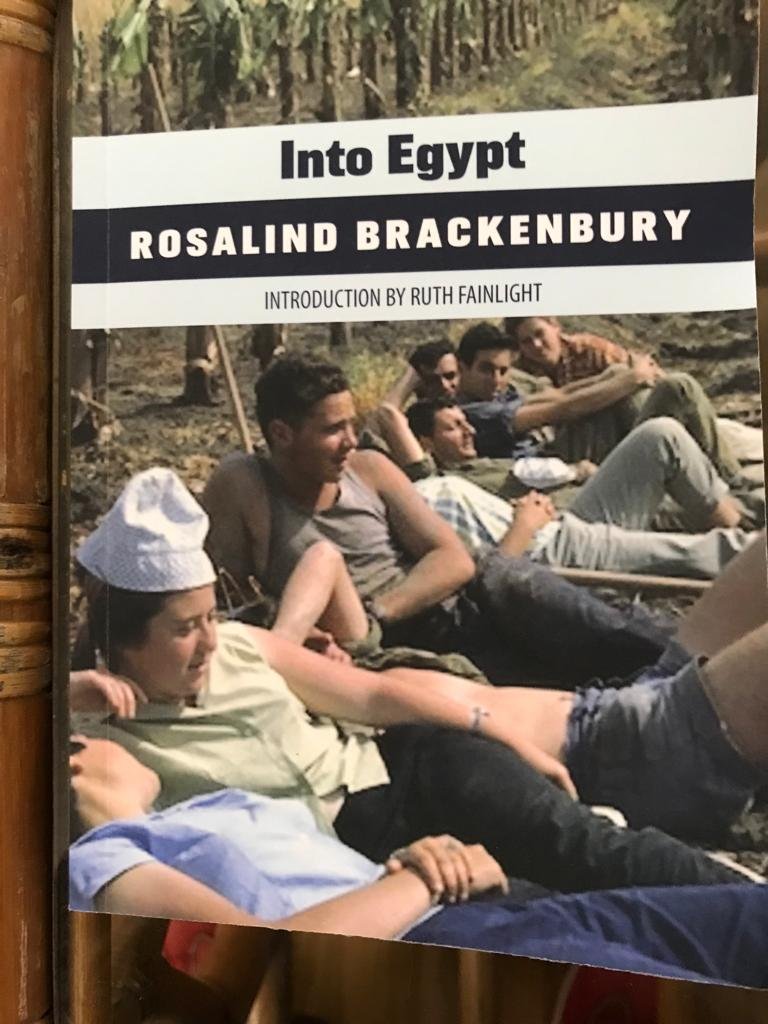

I was astonished to hear recently that the Times Literary Supplement had given a whole page review to my three earliest novels, written in the 1970’s and re-published recently by Michael Walmer. The critic, who has to be a lot younger than I am, wrote at length and very even-handedly about each book. Then she brought up the question of whether novels from the last century were worth re-publishing. She made a distinction between re-discovering and re-visiting novels - one that I found hard to grasp. Mine were to be re-visited, from a sort of nostalgic viewpoint but not re-discovered. So no, they were not any kind of lost classic - but they weren’t bad about being young and female and presumptuous enough to think that the world might be your oyster in the aftermath of the 1960’s.

Now of course I can’t tell whether my own work is worth anyone’s attention or not – I never could, as any writer would probably admit. You hope, of course, to improve with age – not necessarily true, but possible. You get better at most things – cooking, playing tennis, juggling three balls in the air – if you practice them every day. Sometimes, a book will leap out of the past – Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale”, never imagined by her in the 1980’s to be a foreteller of 21st century America. It’s all a bit of a toss-up. As a writer, you can’t know. Will this book last? Will what you wrote at 25 or 30 have anything to say to people when you are 80? Were you right about anything? Does it matter? You throw your hat in the ring, over and over, and take a chance on it each time.

One interesting fact is that the original reviews of these three books in the TLS were very different from the recent one… Link to the review here.

I’m in Venice, after a series of changed plans and an unexpected invitation. It’s quiet. No traffic, no sirens, no ambulances, police cars, no planes over head. What a relief…

From my window – from my bed even – I see the campanile of S. Marco, jutting up behind the gardens and the garden wall, over the roofs of the city. The gardens are green and have three identical garden sheds with green doors. Allotments, I wonder? Walled gardens at the heart of the city. A blackbird sings, and I can hear every note. Wet orange flowers spill over the wall, and a vast magnolia is in bloom. Rain today, and people with umbrellas on the bridges, patches of color in the gray. I walk down our alleyway in Dorsoduro, turn left and along the canal to where my hostess and I had our first glasses of prosecco last night to welcome me here. I go on to visit the church of S. Raffaele and find the little sculpture on the outside wall, the angel with folded wings and the boy Tobias and his dog. Venice is cool and gray and damp and there are few people around as I walk towards the Zattere and along it as far as the Ca’ Foscari university building. Huge reconstructions are going on everywhere. It’s a city continually under repair. The waves slap up at the waterfront and there’s plenty of boat traffic, but there are no cruise ships. They have been banned from coming into the city waters. Hurrah!

There’s no need to go anywhere, do anything, be anywhere, see to anything – the great gift of free time, in a city I love, has been my most unexpected and wonderful birthday present of all. R. and I meet for drinks and at meal times and eat salad, prosciutto, artichokes and flat little white peaches. We’re here ‘to work’ which may mean spending a lot of time not doing anything very much but letting wells refill, thoughts wander, time pass, ideas come and go – and not having any other considerations except to feed ourselves. At our age, we know we don’t have to produce anything, justify ourselves, compete or even try.

I never dreamed of having this time in Venice, on a quiet street, in luxury – with a huge bed, an equally huge bath tub, a desk covered in Morocco leather just like my grandfather’s, and uncounted quiet hours, to do or not to do – to just be. To lie in bed and look at the campanile, for as long as I like. It’s a writer’s dream.

Affectionately, Ros